Pulque magic part I

the drink of Mexico

Worn out, at the little blue and white pulquería on the busy avenue, alone in the gloom but for a scattering of men, workers, on their lunch break, or loafers whiling away the afternoon, I took a drought of the natural pulque which I had ordered on a whim and the taste was so fresh and clear, the liquid brilliant white, like it had just been excreted from the heart of the maguey and blended in vats in a country room, an inexplicable joy came over me. I could not at first understand the source of this outpouring; an image flickered and died before I could catch it. I took another sip. I closed my eyes and communed with the warmth and rest that was inside this living center, a liquid that is literally alive and contains not only a personal history but the history of a culture and in drinking it there was the promise of the release of everything contained in it and in me. I found in its taste a day that I had forgotten. I saw it spring up in front of me as if it was happening for the first time.

We pull off the highway into San Rafael Tepatlaxco. It is dia de la gracia. We step out to stretch our legs. A truck passing by dumps water on us. It isn’t holy water, but water from the tap. It is hot, the sprinkling isn’t bad. Today there is no plan. The landscape is dry, and empty, only nopales stand by the side of the road. We pass the Pantheon de San Rafael and from there rises up Pulquería El Jefe that has a canopy with shade and a wall painted with bowls of pulque and colored birds.

Outside sit a few men with full cups of milky liquid. They nod. Their full vessels are the realization of a long journey.

It began when Quetzalcóatl, the great feathered serpent god, met Mayahuel, goddess of fertility, in the sky. Crazy in love, they descended to Earth as intertwined branches. Mayahuel’s grandmother was not having it, and ordered her granddaughter’s death. Heartbroken, Quetzalcóatl buried Mayahuel’s remains — and from her grace emerged the maguey plant, a centre of Aztec culture and cosmology.

Scientists date the origin of the agave genus, to which the maguey belongs, to about 10 million years ago. Several varieties of the sacred maguey plant are used to make pulque including Agave salmiana, Agave americana, Agave atrovirens and Agave mapisaga, all commonly known as maguey pulquero.

Incredible those maguey succulents must grow for at least 10 years to reach the moment when they produce the sweet sap, honey water, aguamiel, the source of pulque. The signal of maturation is when the quiote, or thick stalk shoots up from the maguey heart. It will send out small branches on which flowers bloom. The quiote is an indication that the maguey is ready to reproduce, and that sugars will be redirected away from the maguey heart to feed its growth. The maguey only blooms once in its lifetime. Soon after that the maguey dies. To prevent the sequestering of precious sugars needed for fermentation the plant is quickly castrated; the quiote is chopped far before it nears its full height of 10 metres, and before it blooms. Before death the plant will be coaxed to produce maximum quantities of aguamiel.

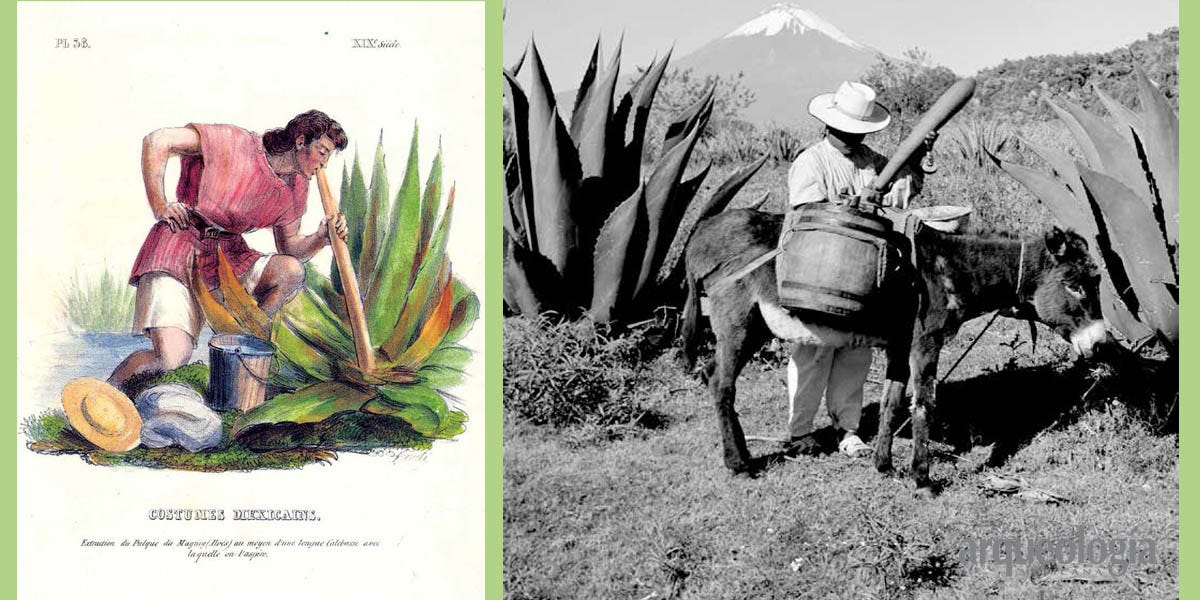

After the quiote is chopped begins the real work of the tlachiquero (the one who harvests the nectar). He removes the leaves until he reaches the heart of the maguey. He cuts a shallow cavity where the aguamiel will collect. He layers the leaves on top as a cover for a period of rest and sap production. In this time the sugar concentration will increase. Once ready, the cavity is regularly scratched in order to stimulate and increase the production of aguamiel, to prevent healing, like removing a scab on a wound so it will continue to bleed.

The sap can be collected for 2-6 months before it dries up and the plant dies. From each plant approximately 250-350 litres of aguamiel is produced, its life’s work.

The tlachiquero leaves his bed before dawn to collect the aguamiel from the maguey. He brings a hollow gourd perforated at each end (el acocote), a bucket, and a sieve. To one end of the acocote he places his lips and submerges the other end in the centre of the plant, where the pool of sticky sap is collecting. He sucks up the aguamiel with his breath and releases it into the sieve through which it strains into the bucket. Depending on the climatic conditions, the humidity and the altitude, the maguey may produce a different volume of aguamiel, anywhere from 3-10 litres in the morning, and another 3-10 litres at night when the tlachiquero returns for more. He drinks some himself, a half litre each day. It keeps him young. It is full of medicinal properties, good for stomach health, it counters cough, and has a flavor which is sweet and green.

Nothing of the plant is wasted. The maguey flowers are a rare delicacy whose petals are consumed before they bloom, and embitter. The taste is similar to meat and an excellent source of protein. The leaves wrap barbecued lamb as it is smoked. The white root is animal feed. The fibers in the leaves are very strong and can make rope or sew leather shoes or saddles. The dried trunk of the dead maguey, mesote, is a carbon to make fire.

Watch out for the zorillo and tlacuache who steal the aguamiel.

Despite the amount of time and work that goes into the production of aguamiel it is sold for very little, about 20 pesos per litre (CAN$1.60). From the source it is transported in wooden barrels or in bags made of goat skins to large barrels in the tinacal, or fermentation room. The fermentation process begins by the addition of the “seed” (a proprietary recipe of natural microorganisms from the maguey and past batches, like a sourdough starter). Like a natural wine, the mixture of microorganisms involved in the fermentation process are those naturally occurring in aguamiel and those incorporated along the way. But unlike a natural wine, three types of fermentation processes are happening: alcoholic of course, but also acidic and viscous. The pulque must continually be fed with fresh aguamiel in order to prevent the mixture from becoming overly acidic or viscous. The pulque always wants more aguamiel. It is a living drink. A good pulque ferments more slowly, and has a constant supply of fresh aguamiel and its sugars. This is why traditionally pulque production and consumption cannot be far from where the maguey grows. Pulque is mostly made by small producers in the states of the Central Mexico plateau. The final product is 2% to 6% alcohol, similar to beer.

It was once a drink to be shared and passed around the circle. Now everyone gets their own glass. Inside the pulquería El Jefe the milky liquid is ladled from jars set on blocks of ice by a pulquero in jean overalls, a sombrero low over his eyes. There are two options, soft or strong. The room is dark and I can barely see a foot in front of me as my eyes adjust from the noon glare. Gradually two men sitting on a bench against the wall materialize. I take pictures of the black and white photographs of movie stars tacked on the rough walls of cement blocks. One of the old men asks me if I am making a documentary of Tlaxcala, that I should do so and can talk to him. Every time I take my camera out in this town they ask me to commit to the role of the documentarian, maybe because they know there is a story to tell and that I am capable of listening.

He tells me that he has been drinking pulque for fifty years. He is dedicated to working the fields. Every day they take a break for lunch to drink pulque, and then they come back to work with pleasure, with gusto to work the fields. They produce a lot because the pulque gives them strength, and also, recreation, amusement, rest.

Do you see the color in my cheeks? Like I’ve been to the beach.

The taste, he tells me, is acidic, or like ayocotes, a starchy, creamy white bean that tastes like a potato. Or maybe he’s saying that he grows ayocotes in the fields. He is speaking fast with the country accent. I try to keep up.

He says that pulque should not be baboso, slimy, like a snail. That it should never touch metal, and it should be drunk from a jicara, a gourd. And that Christ died today at 4 in the afternoon.

He is done his pulque, he takes my leave, climbs on his bike and goes off down the road, back to fields, or anywhere at all because it happens to be a holiday.

I go outside and sit in the shade of a canopy to drink my pulque from the clay cup with painted flowers. The pulque is thick but not baboso, cold, with a flavor a little like fermented oats, a tang that is yeasty, slightly fizzy, bright, and distinct. It is good, fresh pulque. Some may not like it. But I have not tasted anything better for this wrinkle in time.

-TO BE CONTINUED-