Toreros Muertos

wine-skin and cigars

Long before moving, before I could choose to move anywhere outside my parent’s house, I read about Mexico City. The place occupied my imagination. As a teenager I was obsessed with Jack Kerouac, and particularly his less known, skinny little free-associative novel Tristessa, about living in Mexico City unrequited in love with a junkie.

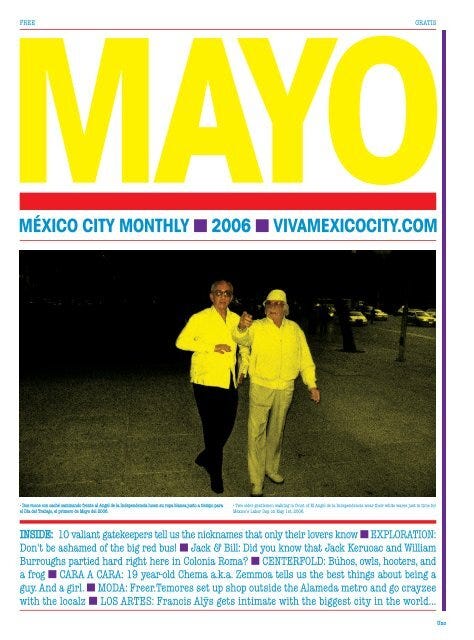

I was also a reader of the long defunct “Mexico City Monthly” available for free at American Apparel with articles printed in both English and Spanish. I would pick it up each month from the Granville Street location in Vancouver, and plagiarize the Spanish for my homework assignments.

One month there was an article on the Beat writers with the addresses of where they lived and partied in Colonia Roma. So when I first came to Mexico City at 24, I moved to Roma, not unlike most other foreigners, and did my pilgrimage to the house where Tristessa was written. I found a boring brick complex, with nothing left of the derelict Porfirio Diaz era apartment Kerouac must have inhabited. I rented an apartment near Plaza Luis Cabrera on Zacatecas, the Beat hangout spot. I was like the narrator in Tristessa, up for any adventure, wanting to be robbed.

“…you had to jump over a ditch to get your drink and the bottom of the ditch was the ancient lake of the Aztec”

— Jack Kerouac on Mexico City, On the Road

“Kerouac never took Mexico very seriously,” said Jorge García-Robles, a Mexican editor who has written on the Beats. “It was a symbol more than something real.”

Today the Beat fascination feels passé/out dated/just hits different. It was still cool maybe when I first arrived in 2015 and met some American and British artists and writers one night, who seemed kind of like wannabe Beats, they were into Antonin Artaud, and other esoteric tastes. They were milling around in the scene, some translation work here, selling paintings to narcos there. They told me I shouldn’t be working in a bar, that I should pursue something higher as befits my class. Being from the Global North and doing blue-collar work in Mexico was “unseemly” the American artist told me. That is the precise word he used, and he would not be emboldened to say it today.

The Beats were all masculinity, wonderment, stimulation, mystification and privilege. In an apartment above the present-day cantina called Krika’s (Don Beto), then known as the Bounty bar, William Burroughs accidentally shot his wife Joan Vollmer instead of the target apple on her head. Without her death he said he would never have become a writer. So it was worth it?

The images of things still influence my choices and interests in the real world. I can’t grow out of that.

Its 2024 and I went to see the bullfight at the Plaza de Toros because of Hemingway.

I wanted to drink wine out of a wine-skin, the bota de vino, like Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises.

“The man who had wanted to pay then bought me a drink. He would not let me buy one in return, but said he would take a rinse of the mouth from the new wine-bag. He tipped the big six litre bag up and squeezed it so the wine hissed against the back of his throat.

All right, he said, and handed back the bag.”

- The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway

The controversy around the bullfight in Mexico City kept us at the edge of our seats. It had been suspended since June 2022 for animal cruelty activism. First the season was a go, then again suspended, the local judiciary caving to protestors, and then it was back on and there would be bullfighting after all. We joked about the protestors eating tacos, and bought our tickets for a Sunday corrida de toros.

The stands of Plaza México are very steep, almost vertical, and the pitch where the action takes place is below ground, a pit. You don’t get a sense of the space until you enter the stands and it takes your breath away. It is the biggest bullfighting plaza in the world. There is space for 42,000 people, and that Sunday there were at least 30,000 in the crowd.

Our seats were for the boxes midway up. Old, heavy wood cubicles with protection from the sun, each bench with room for four, three rows going up, penetrated by the smoke of a hundred years of cigars.

Everyone was wearing a uniform of wide-brimmed hats and jeans, a ranchero look, crisp blouses, some with vests.

Before the bull is released into the ring they pull up a signboard with its name, age, weight and the ganadería brava (breeding farm). There was “el Dentista” and “el Pajarito” (the dentist, the little bird). The bull runs around and the vigor of a thing so alive is an awesome sight, more when you know that in the ring there is death waiting. On his parade around the ring El Pajarito, jet black, flew into the stands like a little bird and thrashed his deadly horns among the public. The next day it was on the news. “The bull jumped two meters. My pregnant wife with my son on one side, on the other, my father and my mother”. No one was too hurt.

It is a performance of life and death. First the bull must be weakened. If not, the fight would go one for hours he is so strong. A rider in medieval get-up on a horse in matching quilted skirt and blinders pricks the bull with a lance, drawing blood. The idea is to wound the animal, but not too much that it becomes too slow to put up a good fight.

The matador embellishes every movement. At times he curves his back when he shakes the cape, contorted, the lumbar spine wildly concave. When the time is right there comes the move I like to call the praying mantis, where the torero has a stake in both hands, in position with his arms up, prancing slowly not to spook, he stalks the bull, then suddenly springs upon his prey, and, if successful, sets both blades into the back.

There is play with the cape, and a lot of style. The audience shouts ole when a sequence is particularly smooth, the bull dives and the bullfighter gets dangerously close, again and again, ole, ole. The finale is when the skill of the torero is on trial. The noble bull deserves a quick death. The sword must pierce all the way through the muscled back to the heart, and with that the bull will fall to his knees and go down instantly. The skillful gesture is often fumbled. It can get ugly. In some fights the bull is pricked repeatedly, a torture, before he finally gives up his life. The audience is angered to see the lack of respect in an inept performance, and jubilant at a quick sentence.

An orchestra plays throughout, punctuating the highs. It is circus-like, a mocking march, originally for military parades, once used between comedy acts, musica pasodoble, brass and drums from the 18th century. What struck me most was the clean-up scene between each corrida. The music plays and many toy soldiers appear (tiny from the distance) to sweep the course smooth for the next round. Caretakers pushing tiny wheelbarrows with dirt to lay. They work industriously in their costumes. The corpse is set upon a wheeled pallet and dragged out of the ring by two horses with blinders on. The contrast between El Pajarito jumping into the stands one moment, next a body pulled by horses is a striking show of fate.

There was a party atmosphere in the crowd. People called out jokes across the plaza and could be heard despite the size, as the architecture amplifies sound. My Hemingway dream was about to come true. A guy in the next box leaned over and offered me a drink from his bota, wine-sack. Maybe his generosity is because I’m a foreigner, one of the few of the thousands in the arena. He passed me the kidney shaped bag made of skin and filled with red wine. I didn’t know how to drink from it, I almost touched my lips to it, but he demonstrated that I am to squeeze, and squirt the liquid in a spigot into my open mouth. I took a deep pour. The wines-sack allows you to share your drink in camaraderie with the people around you without having to touch your lips to the same glass or bottle. The wine-skin and the cigar-smoke are the taste of the bullfight.

“A Basque with a big leather wine- bag in his lap lay across the top of the bus in front of our seat, leaning back against our legs. He offered the wine- skin to Bill and to me, and when I tipped it up to drink he imitated the sound of a klaxon motor- horn so well and so suddenly that I spilled some of the wine, and everybody laughed. He apologized and made me take another drink. He made the klaxon again a little later, and it fooled me the second time.”

The bullfighting season was over in Mexico City. We decided to go to Tlaxcala to see the bullfight at a smaller plaza. The night before the fight we spoke to an old man who was a carnicero or butcher all his life. He told us that the bull is not thrown away after death but sixty percent of the meat is good. As soon as you get the bull, you have to strain the blood. They all drink glasses of blood. If you don’t drain the bull right away it turns black. It tastes bad but you don’t drink it for the flavor, it is healthy, full of good properties. Plus you give it to people and they scream ahhh! No they don’t waste anything, all of the entrails, all of the parts of the animal. A 400 kg animal.

The next day we entered the smaller ring of Tlaxcala. We are much closer to the bull. The plaza is typical, it could be found in a town in Spain. First there was a corrida on horseback and the horses are incredibly nimble, and beautiful. The torero switched horses four times and each one was more magnificent than the last. These fights seem like cheating because there is no real risk for the bullfighter. But the performance was appreciated by the crowd; they took out white handkerchiefs and waved them in approval.

The sublime comes from this game of survival. One of the two exits alive, I was soon to learn there is a real risk. Zapata is back in the ring, he was also there at the Plaza Mexico in Mexico City. The bull he meets is agile and incredibly fast. A worthy adversary. Everything is going well, Zapata in form in his signature dark coat and pants with red inner lining peaking through. The band is playing. And then something terrible happens. The bull is angry; he picks Zapata up with his horns and tosses him to the ground. Time slows. He stamps at the man under his hooves, and appears to trample him. The assistants finally are able to distract the bull with the colored cloaks and when Zapata stands up his face is covered in blood.

It’s dead quiet. It seems that there will be no more fight, that there has been a bad injury. But Zapata brushes himself off and declares that he is ready to continue the fight. The blood was from the bull and he had escaped a horn in his side, a hoof on his spine. He is intact, miraculously. Zapata returns, quaking, to finish the bull. Once more they come face to face, and the intelligent animal does something which chills me. The bull paws the ground with his forelegs, gathering up dust, as if to say, I’m ready for you, I have you, I know you are afraid and I know your weakness. Then as they begin to dance the air fills with singing voices from the church next door, the steeple of which towers over the pitch. The singing is cut by the siren of an ambulance passing on the street. It all feels very mystical, then Zapata finishes the bull with an elegant thrust to an uproar of applause and ole.

“Have a drink ?”

“All right,” he said. You can’t get this in America, eh?”

“There’s plenty if you can pay for it.”

What you come over here for ? ”

“We’re going to the fiesta at Pamplona.”

“You like the bull- fights?”

Sure. Don’t you ? ”

“Yes,” he said. “I guess I like them.”

After a few drinks from the bota my friend and I got to talking. Once we are back at the country house in the hills we opened a cold bottle of a Mexican rosé, my favorite for the price point and quality, from L.A. Cetto in Baja California.

Is the bullfight sport or art?

My friend tells me that the movements are meant to cause an emotion, rather than achieve an end. Therefore it’s art. There is a stylization of the interaction with the animal. Even the killing is done stylishly. They are looking for perfection. It is a performance with the bull, a performance of war, like a gladiator. If you see a bullfight you will have emotions every second.

If you want to see death you go to a slaughterhouse, he continues. The corrida is about survival. One of the two exit alive. It is not about winning or scoring. The trophy is to dominate the other being.

The two players are not in the same condition, like they are in sport. The movements are not for the purpose of winning or scoring. They are to entertain, like performance art.

But, I argue, what about the recreation of the world, through the recreation of the medium? In the bullfight there is no innovation. No development of an individual language that speaks a universe. There is a sequence of movement that changes very little since the beginning of the sport. It does not evolve according to the player; there is an outcome that is planned for, a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order. It’s a ritual, a stylized performance of skill, a sport.

We cannot agree and argue into the morning.

There are no happy endings in The Sun Also Rises but there sure is a hell of a rush. In my bullfight story I end up falling asleep on the couch. I wake when the sun comes up. More real than symbol.

Friends I hope you enjoyed this story. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. This is a project of love, but I need your support to continue to create these careful articles. If you can’t do a paid subscription, please share the blog with anyone who you know who might like to drink, escape, or imagine.